Maile’s Meanderings

If you enjoy this content, please make a donation by clicking on the button below.

With the help of many fine botanists and innumerable helping hands, both paid and volunteer, Amy’s dream of an ethnobotanical garden flourished. The plants are flourishing, their roots firmly anchored in Kona soil tilled by generations of Kona families.

According to online accounts published by Hawaii Volcano Observatory and USGS, a series of earthquakes announced an eruption on April 10, 1926.

For Kona’s fast growing Japanese immigrant population, Daifukuji was a welcome glimpse of home. How comforting it must have been to see that high peaked roof and an altar gleaming with golden lotus blossoms, to hear the notes of the temple gong ringing in the air and to breathe the familiar scent of incense once more.

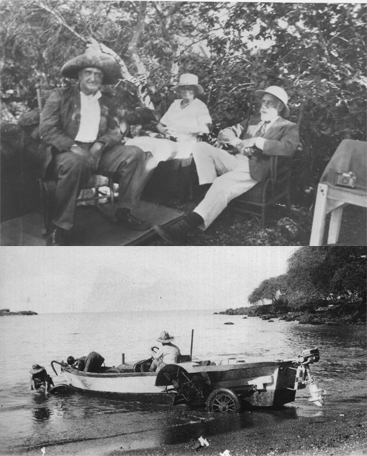

In September of 1954, exactly sixty years ago this fall, four year old Martha Elizabeth Greenwell (M.E.G.), affectionately known by her family as “Meg”, unveiled a large granite monument erected in honor of her late paternal grandfather.

Author Isabella Bird said it best back in 1873 when she wrote a letter to her sister Henrietta trapped in somber Scotland: “It is a joyous green; a glory!” Isabella happened to be riding across the lower reaches of Mauna Kea at the time, but her observation is as spot on now for Kona as it was then for Hamakua. “Whenever I look up from my writing, I ask , Was there ever such a green? Was there ever such sunshine? Was there ever such an atmosphere? And Nature – for I have no other companion, and wish for none – answers,’ No’.”

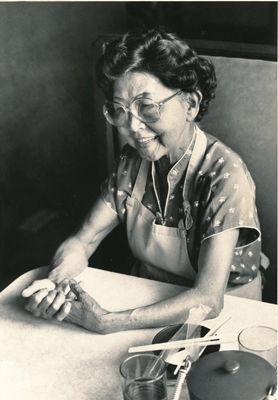

In 1933, Kealakekua Bay was the setting for the annual Fourth of July canoe races. Eager spectators gathered at Napo`opo`o Beach, in those days a wide expanse of silky sand, to cheer their favorite teams to victory. During the festivities, a new song written in honor of the occasion was sung for the first time in public. As unfamiliar lyrics rang out over the water, smiling hula dancers swished to and fro, laughing as they imitated swimming fishes and eating two-finger poi with their nimble fingers.

Surrounded by a moat of naked lava, Honaunau's emerald green coconut crowns now stood out for miles. Enthusiastic young park rangers supervised the dismantling of the core of great `Ale`ale`a heiau on the point. With my intrepid mother once again, we crept up wooden ladders and teetered on rickety temporary bridges set up for visitors to peer into the heart of the temple. I was happy when the rocks were put back in place because that structure was and is for me the epitome of a heiau, a classic beauty of the pure Hawaiian type.

Cowboys, cattle and horses have added a bold, bright chapter to the last two centuries of our district's history.

In 1917 the U.S. Congress approved the 18th Amendment to the Constitution which banned the import, export, manufacture, sale and transportation of alcohol. When the new law went into effect in January of 1920, if Kona police had caught sight of Hayata delivering sake up and down Mamalahoa Road, they would have arrested him. The profitable importation of Masamune sake from Japan was deemed a crime, much to Dr. Hayashi's chagrin.

Hail Konawaena, pride of Hawaii, we, thy children sing,

Daughter of Pele, Mauna Loa cradled, make us worthy of thy name.

If you have never visited Henry Opukahaia’s grave, I would suggest you do. Young Henry grew up in the shadow of Hikiau, destined for the priesthood if his uncle had his way. Determined to choose his own path, at the age of sixteen year he dove into the waters of Kealakekua Bay and swam out to Captain Caleb Brintnall’s ship the Triumph and hitched a ride to New Haven, Connecticut.

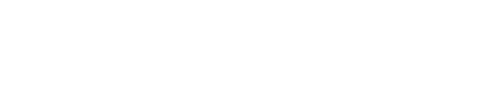

After 70 or 80 years on their feet, most women would rush to retire from restaurant management’s hustle and bustle, but not Mrs. Teshima. Ron Ow once described his grandmother’s management style with total admiration, “She is the iron fist in the velvet glove.”

This stunning display of brightly painted koi announced the important fact the Ashihara family had a boy in its midst!

In 19th century Kona, iron pots were used for lots of things: making booze, boiling oil, washing clothes, and, perhaps, even dying kapa! When early ranchers found tallow making no longer profitable, they passed their pots over to their wives who placed them in their gardens.

Dr. Thomas Augustus Jaggar loved living on an island wracked, ripped, quivered and quaked by volcanoes. He pulled up his roots, firmly twisted into New England’s academic bedrock, and came to Hawaii to learn about volcanoes in nature’s laboratory. He was consumed by a desire to witness, understand, record and predict earthquakes and lava flows like no one else before him (and maybe even since).

“The source of commercial tobacco is a large, sticky-hairy annual herb to about 6 feet high, native of tropical America. Since about 1812 it has been growing in Hawaii, where from 1908 to 1929 it was tried out on a large scale in Kona, Hawaii, as a possible industry.” (In Gardens of Hawaii, 1965)

Built of timber harvested from the Pacific Northwest and cured by a thorough salt water bath in Kona waters, this church has aged with grace and fortitude, withstanding the ravages of earthquakes, termites, and even stubborn houseguests in admirable form. Upon its completion in 1867, it was named Lanakila, Hawaiian for “victory.”

Here is a marvelous photo of the way Kona mauka looked in the middle of the 20th century. We are perched on a ladder or in a tree (how did the photographer get this shot?) in the ahupua`a of Onouli, South Kona, at an elevation of 1,500 feet above sea level.

Within the stone walls enclosing Pulehua homestead were all the trappings of mauka life: butter house, saddle house and small blacksmith shop, cowboy house, house for the cook, koa kitchen and screened pantry to keep out rats, main house, vegetable and flower gardens, and, of course, that all important necessity, a hale li`ili`i (outhouse).

Kahu Billy Paris recalled when freighters arrived in Kailua Bay laden with fuel, a long hose or pipe was connected from the ship to the shore to enable gasoline to be pumped directly into Standard Oil’s large white fuel tank. Fifty gallon drums full of oil were simply floated ashore. When “rafts” of bundled lumber made it onto the beach, Mr. Linzy Child, Amfac’s Kailua branch manager, had men grade (select with no knots, rough clear), segregate, and carefully stack each plank to dry with laths in between each piece.

When I see this wonderful photograph of Kailua Bay, with the black lava of Pa o `Umi emerging from the water’s edge, I am reminded of the passage of time, the briefness of each human life, and the importance of history.

If it were possible to be a fly on the wall of Kealakekua’s cliffs in 1793, we would have seen Vancouver unloading California cattle into canoes in these waters. We would have witnessed Queen Ka`ahumanu and Kamehameha patching up their lover’s quarrel on board Vancouver’s ship. We would have shuddered in fear and delight as explosions of fireworks lighted up the inky night skies over the bay, a popular 18th century entertainment produced by the English for their Hawaiian hosts.